Reflecting on Colorado’s Role in the Fight Against Academic Discrimination

(Excerpt from song by Augustine E. Cordova. Listen here.)

|

En este cielo de sierra, |

In this Colorado mountain |

In 1974, six Chicanx activists were killed in two distinct car bombings in Boulder, Colorado. On the night of May 27, 1974, Neva Romero, Reyes Martinez, and Una Jaakola were killed in a car explosion in Chautauqua Park. All three victims were either current students or alumni of the University of Colorado in Boulder (CU Boulder) and were heavily involved in the United Mexican American Students group (UMAS). At their UMAS memorial service the following day, Florencio Granado spoke passionately about his friends and the injustice that occurred. Less than 24 hours after the service, Florencio Granado, Heriberto Teran, and Francisco Dougherty were killed in a second car bomb on May 29. Antonio Alcantar was also in the car that night, but he survived. Based on law enforcement investigation records, no one was held accountable for killing the six students. There was no justice. “Los Seis de Boulder” is the name given to the two car bombings that took place 50 years ago under suspicious circumstances that remain unresolved.

Prior to this tragic event, the story of Los Seis de Boulder began at CU Boulder during the ‘60s and ‘70s, an era of revolution for civil rights in the entire country. According to historian Jason Romero Jr, the number of Mexican American students at CU Boulder sharply increased between the years 1968 and 1974. In less than 10 years, CU Boulder went from 50 to 1,400 Chicanx students, or an increase of 2,700%. The rapid increase came with many growing pains, but also new opportunities for Chicanx students. During an interview with the Chicano and Latino History Project Agustine Eliseo Cordova explained his experience on campus at this time: “It was beautiful because we had community. And we had to fight for everything that we got; it was kind of a double-edged sword.”

Naturally, CU Chicanxs organized and created UMAS to fight for their needs. As an organization, UMAS focused on several social justice issues, including protesting the Vietnam War, the need for racial diversity on campus, fighting for better financial aid, ending police brutality, stopping military recruitment of students of color, and other important social topics emerging in the ‘60s.

It was this activism for basic student rights that got UMAS labelled as a dangerous and radical social group, and they were carefully watched by school administration and various law enforcement groups. UMAS was formed as an organization to help make CU Boulder a safe place for Chicanx students, but it was met with hostility, and ultimately, lethal violence.

Despite decades of organized student action and tragedies like “Los Seis de Boulder,” inequities within educational institutions remain today. As we mark 50 years since Neva Romero, Reyes Martinez, Una Jaakola, Florencio Granado, Heriberto Teran, and Francisco Dougherty were killed in their fight for justice, I want to reflect on the larger history of educational inequities Chicanxs faced in Colorado. Based on my own personal experience as a Mexican American that grew up in Colorado, I know that important Latinx and Chicanx history continues to be neglected and racial tensions still exist within schools. I was never taught about Los Seis. I was never taught about any local fights against segregation. I was never taught my history.

Rubén Donato a professor at the CU School of Education, has researched Mexican Americans’ schooling experiences throughout American history. Since the late 1800s, he found that Mexican Americans were unwanted in schools, forced to segregate, seen as intellectually inferior and expected to leave school at an early age. However, Mexican immigrants, Mexican Americans and people known historically as “Hispanos/as”, who were some of the first Spanish-speaking settlers in New Mexico and southern Colorado, resisted school segregation and were not passive victims who accepted their educational fates.

|

|

The Maestas children had to walk through dangerous rail crossings in Alamosa on their way to their newly assigned school. History Colorado 2022.17.8 |

Mexican American communities in Colorado challenged school segregation decades before Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. In 1908, the Alamosa School Board purchased land on the south side of town, which board members called “the Mexican side of the tracks,” to build a “Mexican school.” The initial idea for the school was to provide language support for Spanish-speaking students, however, the district enacted a new policy under which all students with Spanish surnames were forced to attend the school, regardless of their English proficiency. After years of trying to work with the district to amicably end this segregation, the Mexican community came together and filed the suit of Maestas v. Shone in 1914.

|

|

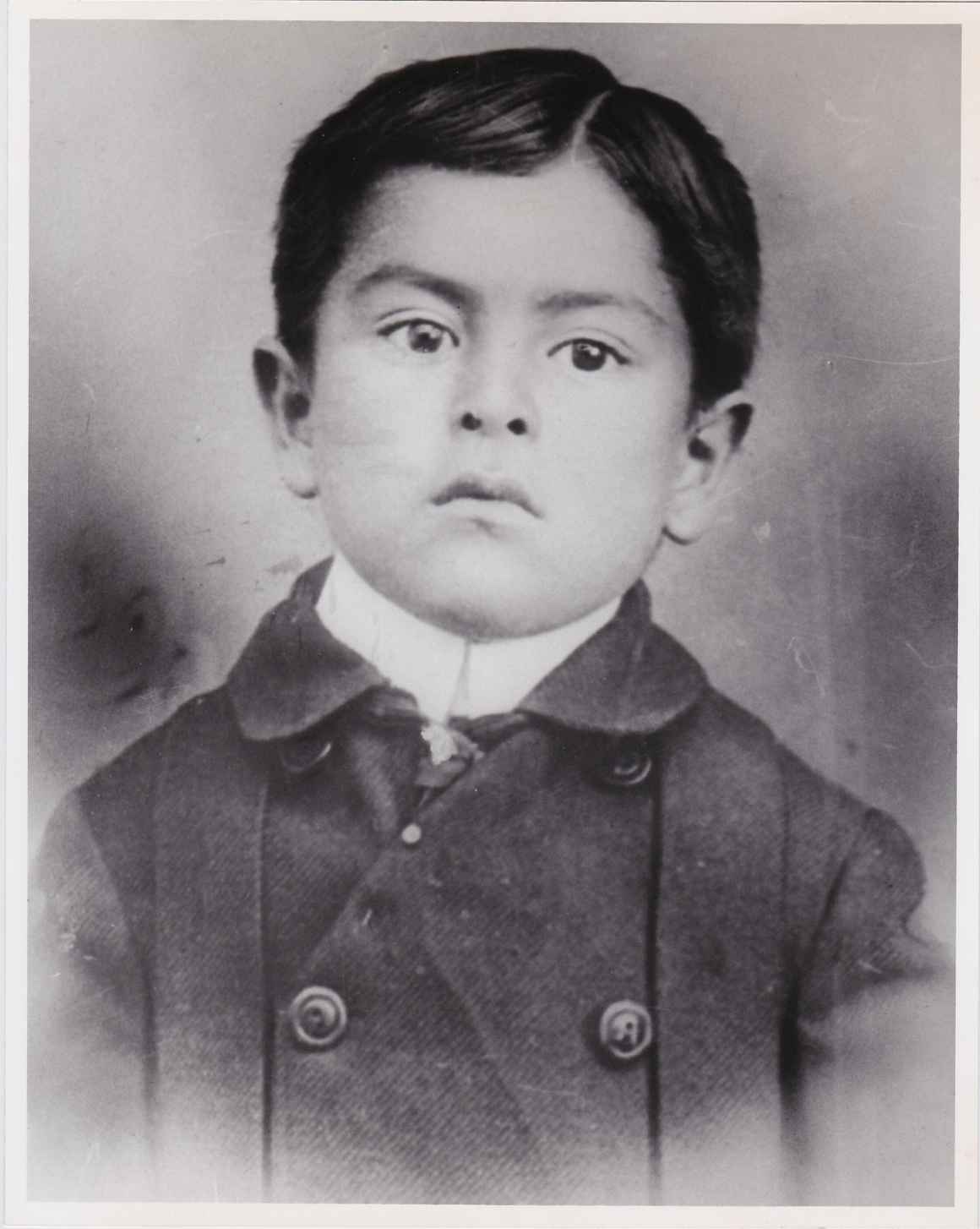

Miguel Maestas, one of the children at the center of the suit. Photo obtained by History Colorado, courtesy of Tony Sandoval and Dr. Ronald W. Maestas |

The main plaintiff, Francisco Maestas, was the father of Miguel Maestas. The injustice his young son faced was especially cruel. According to the lawsuit, Miguel Maestas was forced to walk past an English-speaking school to the Spanish language school, crossing several dangerous railroad tracks along the way. Their attorney argued in court that, in denying children access to the closest school, school officials were making a “distinction and classification of pupils in the public schools on account of race or color contrary to Article IX, Section 8, of the Colorado Constitution.” In 1914, a district judge in Alamosa County ruled favorably with the Maestas family and allowed the children of Alamosa to attend the school closest to their home.

This is one of the country’s first successful legal fights against school segregation, however, it is not referenced in future cases of similar nature. Nearly six decades would pass before Keyes v. School District 1 in Denver reaffirmed that segregation was illegal in Colorado schools — a decision that does not reference the Maestas case or its victory.

Advocacy was not a career choice for me; advocacy and organizing have been a means of survival for myself and my community. From my memory, the first time I witnessed collective power was in 2009 when I was attending a bilingual, yet underperforming, elementary school in Boulder. To address our poor test scores, the district wanted to start over. This meant a new building, a new curriculum, a new principal, and a new staff.

The school organized to protect our teacher’s jobs and our bilingual curriculum. My parents advocated for my right to learn in the language I spoke and understood. I watched my then 10-year-old brother address a crowd, including the superintendent, to defend our favorite teachers. In the end, our teachers were able to keep their jobs without needing to reapply, but the school still underwent curricular and physical changes. I finished elementary school without a playground because of construction and was kicked out of my advanced classes because of class capacity.

To this day, I know my community is not one to accept injustice. We will continue the fight for academic justice, knowing that we stand on a strong foundation built by Black and Brown communities across the state.

Colorado is rich in Mexican American and Chicanx history, and the ACLU of Colorado acknowledges the impact of that history in the fight for civil liberties in our state. In honor of those that lost their lives in Boulder, you can keep their legacy alive by donating to the Los Seis Memorial Scholarship Fund, which provides scholarships to undergraduate and graduate CU students enrolled in CU’s School of Education.

Please note: this link will take you to a third party website, cu.edu, where you will be prompted to enter personal information.

The Chicano and Latino History Project has a robust collection of primary sources and oral histories of leaders in our Latine communities across the state. Finally, I would encourage everyone that is able to watch the documentary “This is [Not] Who we Are” which shares the story of the Black community living in Boulder and sheds light on the institutional racism rooted in the city.